In the US, 2012 was the year of the MOOC or Massive Open Online Classroom. The surprise development of free courses at the likes of the Higher Education elite like Yale, Stanford and Harvard made the headlines and garnered huge excitement and demand, and now the revolution has moved to the UK. Will this apotheosis of democratic learning change HE forever, or will it become merely a freemium marketing campaign for the UK’s cash-strapped Universities?

Will 2013 be the year of the MOOC in the UK? Commentators seem to think that the “Massive Open Online Classroom” is the consequence of the concatenation of increased fees for University attendance, faster and more ubiquitous bandwidth in the home, and a wired public who want to use their free-time and ‘cognitive surplus’ for personal betterment and learning.

These factors, plus the fact it’s the time of year when commentators are prognosticating on future trends and making resolutions means the MOOC concept is gaining in purchase, and the UK is starting to follow the US lead in opening up the academy doors, democratising learning, or grandstanding and marketing competitive advantage, depending on who you believe.

It may be that UK Educationalists have been slow on the uptake about understanding this new generation of students and how they consume knowledge, for all the academic talk about digital natives. Having ten thousand people in a virtual classroom isn’t so alien to a clientele of students used to playing World of Warcraft with thousands of others simultaneously from across the globe. Essentially it’s the same technology anyway, whether MOOC or WoW. However to most academics, raised on the anxiety of ever-increasing class sizes in the real world, and the corollary negative consequence on learning, the MOOC is counter-intuitive.

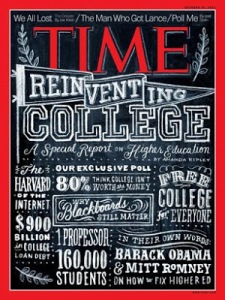

However, probably one of the surprising things about MOOCs is they are a grass roots faculty development- not the corporatization of learning by big business. Stanford Professor Sebastian Thrun co-founded Udacity, one of the 3 big MOOC purveyors in the states, exclaiming “One of the most amazing things I’ve ever done in my life is to teach a class to 160,000 students”.

Of course, Distance Learning is nothing new. In 1858, the University of London opened its degrees to any (male, of course) student, regardless of their location, thus spawning decades of debate about pedagogic quality. In the late 20th century the term Blended Learning arose, almost as an admission that distance learning alone couldn’t deliver the quality of learning. Universities were more receptive to delivering Blended Learning (or Click and Brick as one wag put it) because it maintained their control and need for real estate if you’re being cynical. However with the dominant digital media being the CD at the time, and the nascent internet running at a mere 14k, and being accessible in 1990 to only 3 million people worldwide, of which only 15% where in Europe, distance learning lacked interactivity and couldn’t fulfil the need for a social forum of discussion and debate. Rich Media at the time referred to a 240 pixel quicktime file. It seems to have taken the ubiquity of Web 2.0 tools and social media networks to deliver some of the potential of e-learning.

.

ENTER THE MOOC

Every technology needs a creation myth. The first MOOC was in 2008. A “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge” course at the University of Manitoba was planned with a class of 25 students when it was decided to open it up online for free, merely because they could, and in the spirit of the subject matter. Learners could participate with their choice of tools: threaded discussions in Moodle, blog posts, Second Life, and synchronous online meetings with the course content available through RSS feeds. There was a huge surprise for organisers Stephen Downes and George Siemens when eventually around 2400 people registered. They had just encountered the scaleable and connective possibilities the internet now afforded higher education.

In response, Dave Cormier, Manager of Web Communication and Innovations at the University of Prince Edward Island gave birth to the name, borrowing from the game term Massive Online Role Playing Game or MORPG. The MOOC was born, although there were many more obscure precedents.

But the ‘Massive’ in MOOC had yet to really happen. If in the myth of MOOCs Manitoba was the urtext, then Stanford was the eureka moment.

“In the Fall of 2011, Peter Norvig and I decided to offer our class “Introduction to Artificial Intelligence” to the world online, free of charge…and in the end we graduated over 23,000 students from 190 countries. In fact, Peter and I taught more students AI, than all AI professors in the world combined. This one class had more educational impact than my entire career.” Says Professor Sebastian Thrun who gave up teaching at Stanford to co-found and create free courses for Udacity, explaining “One of the most amazing things I’ve ever done in my life is to teach a class to 160,000 students.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) soon followed with a series of MOOCs entitled MITx in early 2012 with free courses in circuits and electronics, before being joined by Harward to launch edX having together committed $60 million to the project, which saw 370,000 students enroll for free on courses as varied as Computer Science, Statistics, Copyright, Justice, and Greek Heroes. Meanwhile Coursera launched, having raised $16 million in venture funding, and now claims to have 1.7 million students, with courses from 33 of the biggest names in HE including Princeton, Columbia, Berkeley and CalTech, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and from the UK, the University of Edinburgh which currently runs 5 MOOCs of around 5 weeks long. Coursera MOOCs span the Humanities, Medicine, Biology, Social Sciences, Mathematics, Business, and Computer Science.

Can such scaling up of HE ‘products’ work and reap results? Yes it seems, if you exclude grading and forms of assessment (apart from peer assessment or in some cases, automated assessment. Coursera uses peer grading: submit an assignment and five of your cohort grade it, as you do theirs).

Because the learner isn’t assessed, no credits or qualifications ensue. A MOOC participant from say, Harvard can’t say they have a degree from Harvard. That is where the idea of freemium comes in. Will a MOOC prove to be the gateway drug to get bums on seats, bringing those Clicks in to Bricks?

.

HIGHER EDUCATION or HYPER EDUCATION?

Distance Learning, e-learning, whatever the nomenclature, has always suffered from hype. In 1999 John Chambers, the president and CEO of Cisco Systems proclaimed “The next big killer application for the Internet is going to be education. Education over the Internet is going to be so big it is going to make email usage look like a rounding error”. Today the hype is no different.

2013 will see if MOOCs can find fertile ground for adoption in the UK. It could be argued that despite the post-Browne fee hikes in HE learners are not experiencing the financial pain of the average American student. Also the scale and geographical constituency of the HE environment in the UK is very different. Also most MOOC courses seem to be STEM (Science Technology Engineering Maths) based, since it seems they translate best into the MOOC format- with less need for face to face interaction, or iterative practice. In the UK, we don’t yet have the kind of aspirations in computer science and maths, because we don’t yet have a Silicon Valley equivalent to fuel that desire, or career demand.

It may well be that OOCs would be a more realistic achievement, but without the M, would venture capital be invested like in the States? Anyway, in the UK, are our Higher Education institutions innovative enough to leap in and take early adopter rewards? Will the Russell Group be incited into enjoining the fray, worried about losing global market share?

There’s a lot of talk about democratising learning, but is there also a business model predicated on massive numbers, like freemium computer games, that go into profit if only a very small percentage of players choose to buy a wizard’s cloak of invisibility or a ‘power-up’? Will people pay for the accreditation, the extra certificate, the grade that proves their standard of learning? That has to be the end-game of this freemium offer. Or could UK MOOCs be seen as a loss leader to entice high fee-paying overseas students, to entice the BRICs to Bricks (if you’ll excuse the pun)?

Udacity have recently partnered with Pearson, paving the way for certification “now, students wishing to pursue our official credential and be part of our job placement program should also take an additional final exam in a Pearson testing center. There are over 4000 centers in more than 170 countries.”

Coursera, the largest of the big three MOOC aggregators says it may charge between $30 and $80 per certificate, depending on the course, to students who complete successfully. MIT and Harvard say they will likely charge a “modest fee” for the opportunity to earn an edX certificate. Udacity, on the other hand, seems to want to make its money from finding jobs for its students, and promote them to employers. In Silicon Valley, headhunters often get paid finder’s fees equivalent to 20 percent of a software engineer’s starting salary, which could mean around $15,000 per recruit.

.

ONLINE and OPEN

One point that isn’t so well reported- it tends to get lost because journalists and PR like all those big numbers- is that of the nature of openness- the power of the network that the learner builds and develops. MOOCs are social. It’s not the 1970s Open University paradigm of sitting down at home to do your coursework alone and then sending it in.

As online education author Tony Bates says “While the hype about MOOCs presaging a revolution in higher education has focussed on their scale, the real revolution is that universities with scarcity at the heart of their business models are embracing openness”.

There’s probably no better introduction to this aspect of the MOOC than Dave Cormier’s YouTube clip. To Cormier (who originally coined the phrase) MOOCs promote participation, not consumption, and life-long networked learning. They’re a way to connect and collaborate. A MOOC is not a course but an event where people can get together in communities of practice. The course content is distributed not centralised – it’s what each learner finds out and shares from across the internet, not the University’s course content stored in one central location. All those Tweets, Blogs, Vlogs and websites knit together to make a knowledge corpus that can be approached and negotiated from different angles, with learners on different paths. Unlike a classroom course with a steady and incremental drip of information, a MOOC has no single path towards completion. To Cormier this allows new ideas and connections to be made, and those ideas are fed back into the network for all.

.

R MOOCS UK OK?

In the UK, December 2012 saw the news that the Open University had created a new company, Futurelearn, which will offer free online courses from UK Universities like Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, East Anglia, Exeter, King’s College London, Lancaster, Leeds, Southampton, St Andrews and Warwick. These Universities were evidently chosen for their high performance in league tables. Futurelearn intends to offer courses in the second half of 2013.

The Futurelearn Company will be able to draw on The Open University’s expertise in distance learning and its pioneering work in accessible education resources. Futurelearn promises to be a single gateway. “Futurelearn will not replicate class-based learning online but reimagine it” says the Press Release.

The Futurelearn Company will be able to draw on The Open University’s expertise in distance learning and its pioneering work in accessible education resources. Futurelearn promises to be a single gateway. “Futurelearn will not replicate class-based learning online but reimagine it” says the Press Release.

It’s clear from the accompanying press releases that the UK government and academia have woken up to MOOCS. The talk is of extending access, opening up research and learning, and giving the world access to the ‘highest quality educational opportunities’.

CEO Simon Nelson (who previously spent 14 years at the heart of the development and management of BBC Online) said “until now UK universities have only had the option of working with US-based platforms.” This appears to be a strong motive- a rearguard action to address the huge traction that successful US MOOC aggregators like Coursera, EdX and Udacity seem to have. Having an early presence in the MOOCsphere seems to be imperative. The fact there seems to be no fixed business plan as yet, and yet a stellar academic cast of partner universities seems to point to a freemium model at least initially. “I’m really looking forward to seeing how students interact, where value can be created, and where people will be prepared to pay for that extra value,” Martin Bean said, adding that any income would be shared with Futurelearn’s members. Meanwhile Mark Taylor, Dean of the Warwick Business School hopes its offering on Futurelearn would “act as a kind of taster” for students who might then consider paid-for courses at the institution. “There is a philanthropic element to it but at the end of the day we have to pay the bills” he said.

The fact that 12 sober and rational HEIs have stepped into this compact seemingly without a business plan or long term strategy seems to imply a number of Deans are waking up and smelling the aroma of Coursera coffee.

However, there are two other elements that might be in play here. Firstly, Universities might at last have finally woken up to the power of analytics. As a regular visitor to UK universities, this author has always been surprised on how little they know about the behaviour and location of their greatest assets- alumni and current students.

Like the relationship between games designers and online players has changed, the fact that valuable consumer/student behavioural data can be harvested and analysed means online or blended learning courses can ‘always be in beta’ like a Game App, and pinch points of attrition and drop out can be identified and changed. Valuable information on where the learner meanders and the obstacles they might encounter can be aggregated and fed back into the course experience.

Secondly, there’s the accessibility agenda, and the fact this might be accomplished via an online presence for those aspirational time-rich yet financially poor digital natives out there. Professor Sir Steve Smith, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Exeter, explains that Futurelearn is a new opportunity to “provide learning in a different way and open up our expertise to new audiences. Online learning is becoming an integral part of what universities do”. Globalism and accessibility seem to be entwined. Cardiff University’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Colin Riordan said: “Cardiff is a global player…This exciting initiative provides a real opportunity to extend access across the world to our high quality education experience.” Accessibility here means the global market.

However, as Doug Clows says in his blog about MOOCs “If someone’s going to be doing it, I’d rather it was the OU, with its 40-year tradition and commitment to opening access to higher education, than a venture capitalist with a commitment only to making money”.

.

HOW WE DIDN’T GET IT RIGHT BEFORE: THE CONVENIENTLY FORGOTTEN HISTORY OF UKeU

Those with long memories (well, a decade) may feel a sense of déjà vu here. The UKeU (UK eUniversities Worldwide Limited) was a company with a website portal that promoted online degrees from UK universities. It was first proposed as a concept by David Blunkett, then Secretary of State for Education for the UK, in a speech in February 2000. UKeU (like Futurelearn today) was to be a broker, an agent for e-degrees, marketing online degrees from British universities and providing a technological platform to make them happen.

Set up by the government of the time with £62 million, and constituting 12 universities (coincidentally the same number signed up to today’s Futurelearn) allied to a tech company to provide the software, by January 2004 it housed some 25 courses.

Unfortunately only 900 students signed up by the time the plug was pulled on funding – thus costing a total of £44,000 for each learner. “People who burnt public money in what was a political enterprise should be censured” fulminated Ian Gibson, MP and Chair of the Commons science and technology committee at the time.

HEFCE, who took a lot of political fire in the months ahead, saw UKeU as a vehicle to invest and prepare UK universities for e-learning. It admitted it had been disappointed in the lack of private finance, but resigned to dismantling the scheme. There is not even a url left to remember it by- this was snapped up and adopted by a UKEU finance company.

Consultants complained about a “lack of focus” in management and said marketing was based “more on optimism than market-led judgements”. Other criticisms ranged from the fact that UKeU ignored Blended Learning, being purely online, and that costs of developing a proprietary platform were more than expected.

It was noted by the Select Committee that too few UKeU staff were appointed with knowledge of e-learning. “UKeU did not have anyone with e-learning expertise in a senior management position. The Chief Executive, had experience of e-business but not e-learning.´

But it mustn’t be forgotten that the early noughties were the time of much optimism and that UKeU wasn’t alone as a grand project that failed. The Open University, a British success story in distance learning in the pre-digital age, also tried to make it in the US and had to admit defeat after losing £9m.

Even Universities in the US had fingers burnt. Columbia University launched Fathom in spring 2000 in collaboration with 14 universities, libraries and museums, including the London School of Economics and the British Museum. Columbia put up most of the initial $20m, which was followed the next year with another $20m. But the paying customers didn’t come. Fathom finally sank in January 2003. Cornell launched the virtual Cardean University; a joint project with the famous Wharton business school at the University of Pennsylvania and a company called Caliber (which went bankrupt); and Temple University, which closed its “for-profit” company without offering a single course.

.

MOOCs: This time it’s personal

There are good reasons to think that history won’t repeat itself. Firstly UKeU was a product of the technocrats of the time, working on a proprietary platform- before facebook, YouTube, flickr, LinkedIn, Twitter. It’s easy to forget that the term “Web 2.0” was first described in 1999 by Darcy DiNucci in an article “Fragmented Future” and readily available platforms and services didn’t exist at the early stages of UKeU’s genesis.

UKeU was based on a broadcast paradigm, a one-to-many approach. It was to be asymmetric, with chunks of video, text, imagery delivered to the learner. Universities also had few digital assets, and what they already owned as assets was predicated around Blended Learning methodologies. Uncoupling this into purely online gobbets would have diminished its effectiveness. We’re also a lot more able to deliver and store dynamic rich media now. Universities can use YouTube or Vimeo rather than proprietary systems. The astronomical amounts of data produced by UKeU at the time now would fit on an a schoolboys hard drive- HEFCE’s electronic archive consists of over 13 GB of material organised in nearly 90,000 files in over 11,000 folders with supplementary archives of a further 5 GB. We’d call that puny now. Ironically and rather telling for the time, HEFCE also have in storage a paper archive consisting of 166 boxes of material. That’s what £62 million got you in old money.

Nowadays, Universities have developed their own experience of distance learning, albeit none announced with the kind of fanfare accompanying UKeU at the time. There’s a sense that everyone is a little cautious this time round, although it doesn’t seem that the ‘supply-driven, not demand-led’ criticism can be levelled at Futurelearn. The demand seems to be in evidence in the US, so why not here?

A revolution in social media and the ubiquity of online devices have meant Futurelearn is behind the curve but keen to catch a slab of market share from Udacity, Coursera and edX, which offer around 230 MOOCs from around 40 mostly US-based institutions to more than 3 million students.

Clay Shirky draws parallels between what happened in the music business with the disruption now underway in HE in his insightful blog Napster, Udacity, and the Academy. “It’s been interesting watching this unfold in music, books, newspapers, TV, but nothing has ever been as interesting to me as watching it happen in my own backyard. Higher education is now being disrupted; our MP3 is the massive open online course (or MOOC), and our Napster is Udacity, the education startup.” He also notes that academic critics of MOOCs focus on issues of quality and a concern that the access agenda has gone too far, forgetting that the MP3 file transformed the music industry for ever despite not being of the ‘high quality’ so many people thought was essential.

MOOCs and Money?

Probably one of the more sober assessments of MOOCs comes from Sir John Daniel in Making Sense of MOOCs: Musings in a Maze of Myths, Paradox and Possibility, written in September 2012. He makes the point that MOOCs have already bifurcated into two distinct types of course- xMOOCs and cMOOCs. xMOOCs (as in edX) were the biggies that impressed us all (and mainstream media) with the large numbers and massive scale yet may revolve around more of a ‘broadcast’ paradigm with passive consumers and a conservative pedagogy, whereas cMOOCs (connective) are more about a pro-active network of learners generating and sharing new knowledge, which is present across the network, not just in the central emanation. By this rationale the MOOCs original genesis was very cMOOC, but the xMOOC’s basis is more about corporate start-up behaviour looking for a monetisation strategy.

To me Daniel’s essay is useful because he points to how today’s xMOOCs are in some way a rehearsal for attempting to maintain university market position in the digital world of information fecundity.

In terms of a wider gamut of motivations other than academic altruism Daniel picks up references to how MITx is supposedly being used as a testing ground for mastering this disruptive technology and applying it to their residential students; one of Coursera’s university’s course offering is fuelled by a fear that there will be a loss of revenue if they don’t contribute; the factor of attrition (it’s not unusual for 93% to drop out before completion) – which makes the numbers the press quote superfluous.

As reporter Jeffrey R. Young says in Inside the Coursera Contract: How an Upstart Company Might Profit From Free Courses “Coursera is following an approach popular among Silicon Valley start-ups: Build fast and worry about money later. Venture capitalists—and even two universities—have invested more than $22-million in the effort already. “Our VC’s keep telling us that if you build a Web site that is changing the lives of millions of people, then the money will follow,” says Daphne Koller, the company’s other co-founder, who is also a professor at Stanford”.

So how exactly will the money follow? It seems Coursera think it may be generated by Certification, proper assessments (as opposed to peer graded), employee recruitment (and other HR matchmaking services), applicant screening for employers, learners pay for extra bespoke tutoring, selling the MOOC platform to companies to use for their own training programmes, tuition fees, and sponsorship. Some of these monetisation strategies can be controlled by the participating university (ie certification) and some by the MOOC aggregator company (eg recruitment). It’ll be interesting to see how these contradictory drivers might be played out in the year ahead.

.

Postscript: DON’T JUDGE A MOOC BY ITS COVER: A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE

I’ve decided to subscribe to two separate MOOCs, one by the University of West Virginia through Coursera, and one from the University of Edinburgh through Udacity, just to experience them myself. It looks like a combined commitment to 15 hours per week. My motives surprised me. MOOCs originally seemed to me to be a great way to learn, and being part of an online community of learners might spur me on more than a textbook or isolated study.

I’ve worked in Higher Education, and have written and designed degree and postgraduate courses and so feel comfortable with the way courses operate, but I admit I felt the excitement of having certificates from these hallowed institutions as a lure, emblazoned on my CV, even if they are without any credits or real qualification value.

The last words should probably go to one of the facilitators of the first MOOC. George Siemens comments in Finally, alternatives to prominent MOOCs, “Even if MOOCs disappear from the landscape in the next few years, the change drivers that gave birth to them will continue to exert pressure and render slow plodding systems obsolete (or, perhaps more accurately, less relevant). If MOOCs are eventually revealed to be a fad, the universities that experiment with them today will have acquired experience and insight into the role of technology in teaching and learning that their conservative peers won’t have. It’s not only about being right, it’s about experimenting and playing in the front line of knowledge”.